GROWING UP WITH CLEFT LIP & PALATE

WRITTEN AND EDITED BY REMI STAMATELLOS

Disclaimer: this is not meant to describe the experiences of all individuals with cleft lip & palate. Instead, it describes my personal experiences via stream-of-consciousness narrative. Content alludes to internalized ableism.

Being a twenty-two year old with cleft lip & palate continues to be a strange experience. For those who do not know, cleft lip and palate occurs when the structures that form the upper lip and palate do not join together when a fetus is developing in the womb. This results in a hole in the soft palate and gaps in the upper lip. I have a bilateral cleft lip, meaning that the lip splits in two places rather than one.

My childhood involved a lot of straw biting, metal wire adjusting, and dissolvable stitches. Surgeries, speech therapy, etc. It was an "every six weeks" trip to Atlanta for an adjustment to an ever-changing face that, honestly, was not recognizable to me.

It's a bit difficult to bring up things like this when talking about my childhood. Most people feel pity, not just for me, but for my mother who had to deal with three cleft lip & palate carbon copies of herself. It may just be difficult to respond in a way that isn't apologetic. I get it. It can be awkward hearing things like this, and I do understand the feelings of discomfort. I am genuinely not looking for sympathy, though. Instead, all I am asking is to be understood.

That being said, it has its shit moments. It may be a primary reason for most of my physical woes. Perhaps my body could not tolerate the stress of multiple surgeries per year, or maybe the genetic code of cleft palate wrote other disabilities into my convoluted DNA manuscript. It shares genes with autism, autonomic dysfunction, and an extensive list of disorders that I have and would likely shock no one. I have long suspected it's the culprit of my sleep apnea.

Having cleft lip doesn't particularly bother me as much as it used to, though. It feels more like a cartoon fist raise, a "god damnit, not you again, you nasty son of a bitch," than a "my self esteem solely depends on how my face is currently structured" kind of thing.

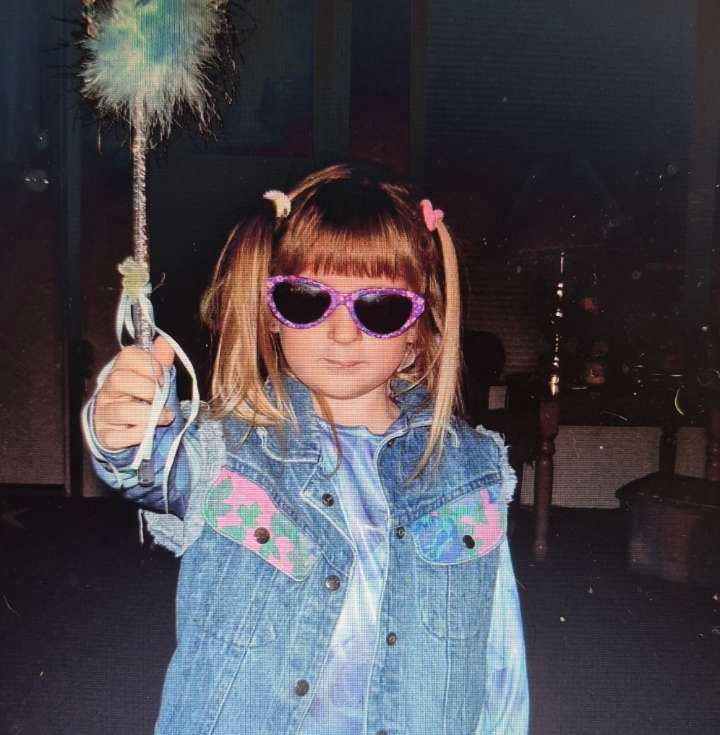

No one had told me that having cleft lip & palate was not the societal standard.

I was in Kindergarten when I discovered that not everyone was a little soldier who frequented the orthodontist's office.

After all, four out of six members of my immediate family had cleft lip & palate. This didn't include both of my maternal grandparents who also had cleft lip & palate. Genetics were not kind to my mother, who was the only one of her five siblings born with cleft palate.

Thankfully, insurance was gracious with us, drooling at the spectacle of two-thirds of a family having a visible genetic disorder. We even got a special mid-2000s-style pamphlet created about our family, detailing our family's case like it was straight from the Guinness Book of World Records.

I would almost describe my discovery of "non-clefters" as a culture shock in some way. Most people are profoundly aware of their own difference, but to me, cleft lip and palate was engraved into my little youngster brain as the only way one could be. The rule, not the exception. Walking onto the bus, finding that I was, indeed, the odd one out, was a humbling experience to say the least.

Although, I was not unarmed against the blunt remarks of curious six to twelve-year-olds. The "what happened to your nose" question was particularly common. I brainstormed with my cousins how to ward off the harbingers of cruel and unusual questions such as this. We settled on the story that I was mauled by a tiger who had very precise scratching techniques.

It was a certain defense that did not completely quiet the confusion and insecurity I felt for myself, who was missing teeth and couldn't quite drink water without it spilling from my nose. I had to be strong anyway. To think of the repair surgeries as holiday routine. If not for my burnt out parents, who I had burdened, then at least for myself.

Now, compared to my childhood, most people do not even notice the small scars inching from my nose to my lips, or the effort I put into articulating each and every word. I am "normal-passing" as one could be, sans the cane and acne. And that is what I wanted as a kid, a sense that what I was experiencing was normal. Or at the very least okay.

But for some reason I find it a bit disquieting, feeling the acknowledgement of my struggle slipping away.

For the unaware, craniofacial issues like cleft lip & palate tend to become system-wide problems. This means I would often get ear infections, sinus infections, and later on, hearing loss. Honestly, it wasn't until late teenage-hood that I realized not everyone celebrated their surgically-inserted ear tubes falling out.

It's a bit comforting in its own way, having things to celebrate that others may not even think about. I looked forward to the pre-surgery mega meal and the post-surgery Mad Libs. I preferred nesting in the recliner to sharing a room with my younger brother, and I enjoyed endlessly rewatching Mulan (1998) and The Princess Bride on the Big TV. No one could tell me I couldn't, because, you see, I just had surgery. And there's a certain joy in that. Joy in figuring out how to eat popcorn without breaking my braces, eating hard candy, and describing to others, in great detail, the dystopian-levels of body horror I experienced. I thought it was funny at least.

There's a part of me that tries to take pride in having cleft palate, the same pride I have shouting my lesbianism into the un-listening atmosphere. There's another part that refuses to let myself struggle with the uglier sides of it, like how I'm riddled with disassociation when I look in the mirror. But I sometimes want to paint my scars.

Perhaps there was no sense in being strong then, and perhaps that strength is the reason I am still here.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Remi Stamatellos (they/them/elle) is a chronically ill, Nonbinary Femme Lesbian and one of The Snapdragon’s founders. They graduated from the University of West Georgia with a B.A. in English and certificate in Publishing and Editing.

Remi primarily works as the editor-in-chief, copywriter, web designer, and events planner for The Snapdragon. Their goal is to give fellow LGBTQ+ and Disabled people the opportunity to share their mutual experiences without the risk of feeling ostracized. Beyond their magazine duties, they love to bake, sing, and fawn over their cats.